Last week, the Ghana Statistical Service released its latest jobs report with data up to Q3 2023. It’s a great report with good data. I encourage everyone to read the report. This short essay highlights some of the key findings from the reports.

Unemployment in Ghana has worsened over the last year

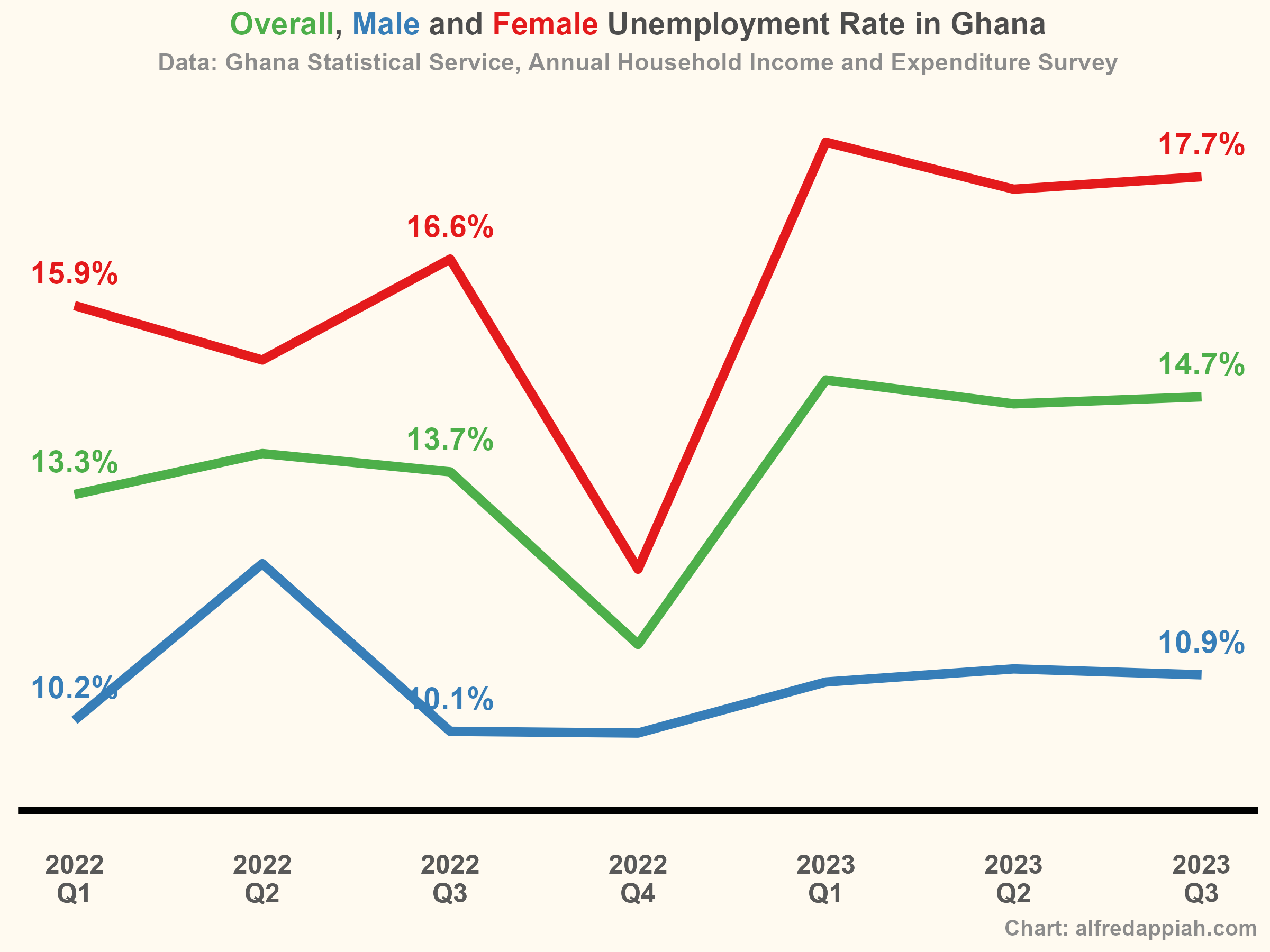

The data from GSS shows that between Q3 2022 and Q3 2023, the overall unemployment rate in Ghana increased by one percentage point. The unemployment rate for females increased more than that for males.

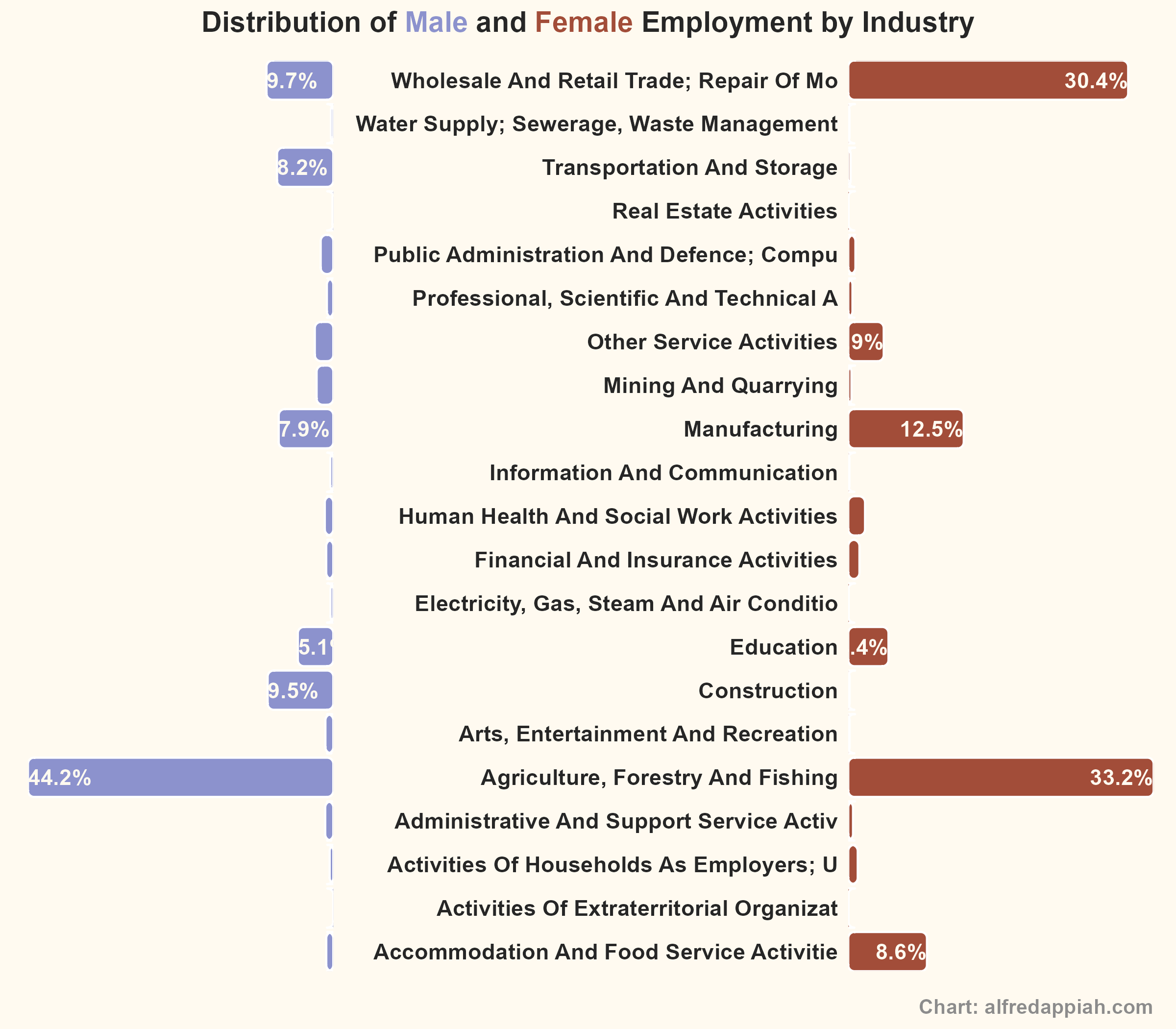

An interesting observation in the unemployment trends is that in the last quarter of 2022, the overall unemployment rate declined significantly, and even more significantly for females. That may be a function of increased employment activity during the festive season. Females are more likely to work in the wholesale and retail trade as well as accommodation and food service industries, than males. Both sectors experience a “boom” in the festive season. But I would want to see Q4 2023 data to be certain that the drop in unemployment in the last quarter of the year is not just a statistical outlier.

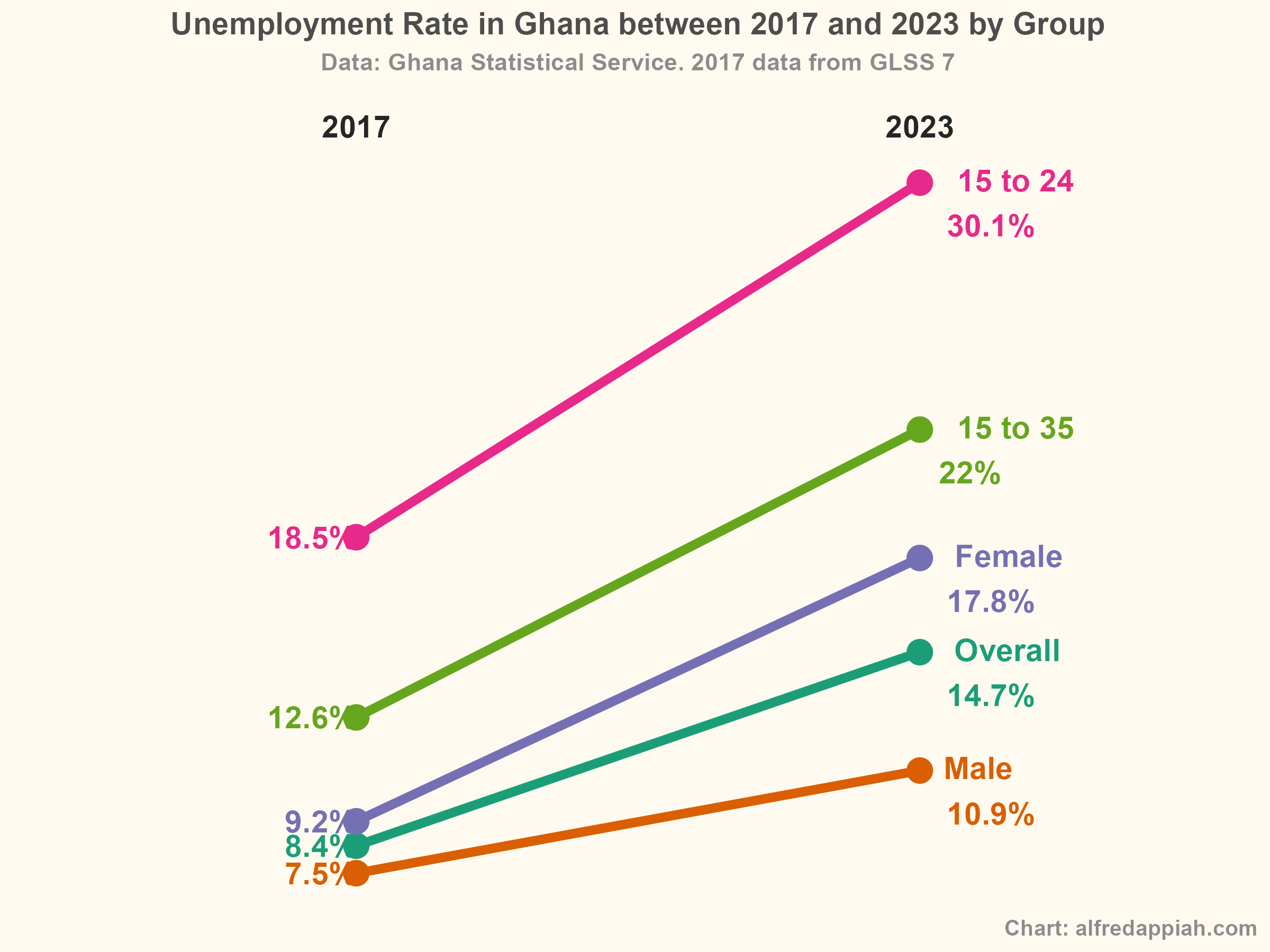

The unemployment situation is worse than it was six years ago and for all demographic groups

If you go down memory lane to look at unemployment rates and compare to now, you get an even grimmer picture. For example, the overall estimated unemployment rate in 2017 (based on the Ghana Living Standards Survey 7) was 8.4%. It is now 14.7%. Male unemployment rate has increased from 7.5% to now 10.9%. The unemployment rate of adult youth (15 to 35 years) has almost doubled in that time frame. That of younger youth (15 to 24 years) has seen an increase from 18.5% in 2017 to 30.1%

But the unemployment rates are even ‘generous’. Given the level of informality in a developing country like Ghana, the rate of unemployment often tends to be understated. Therefore, it’s important to look at the structure of the labour market and the extent to which shifts are occurring as a result of government labour market interventions, particularly towards more salaried and wage employment which can signal advanced economic development.

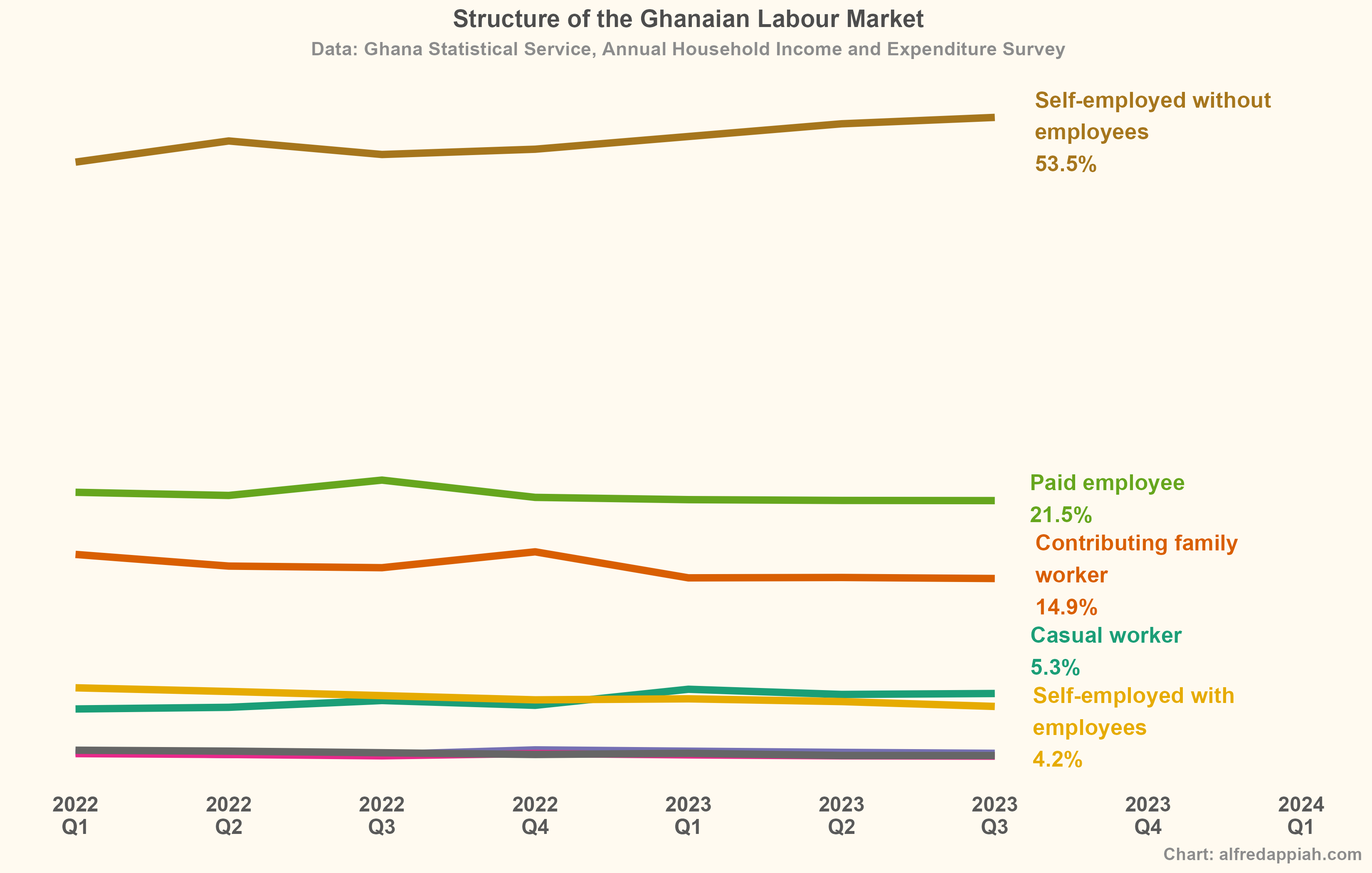

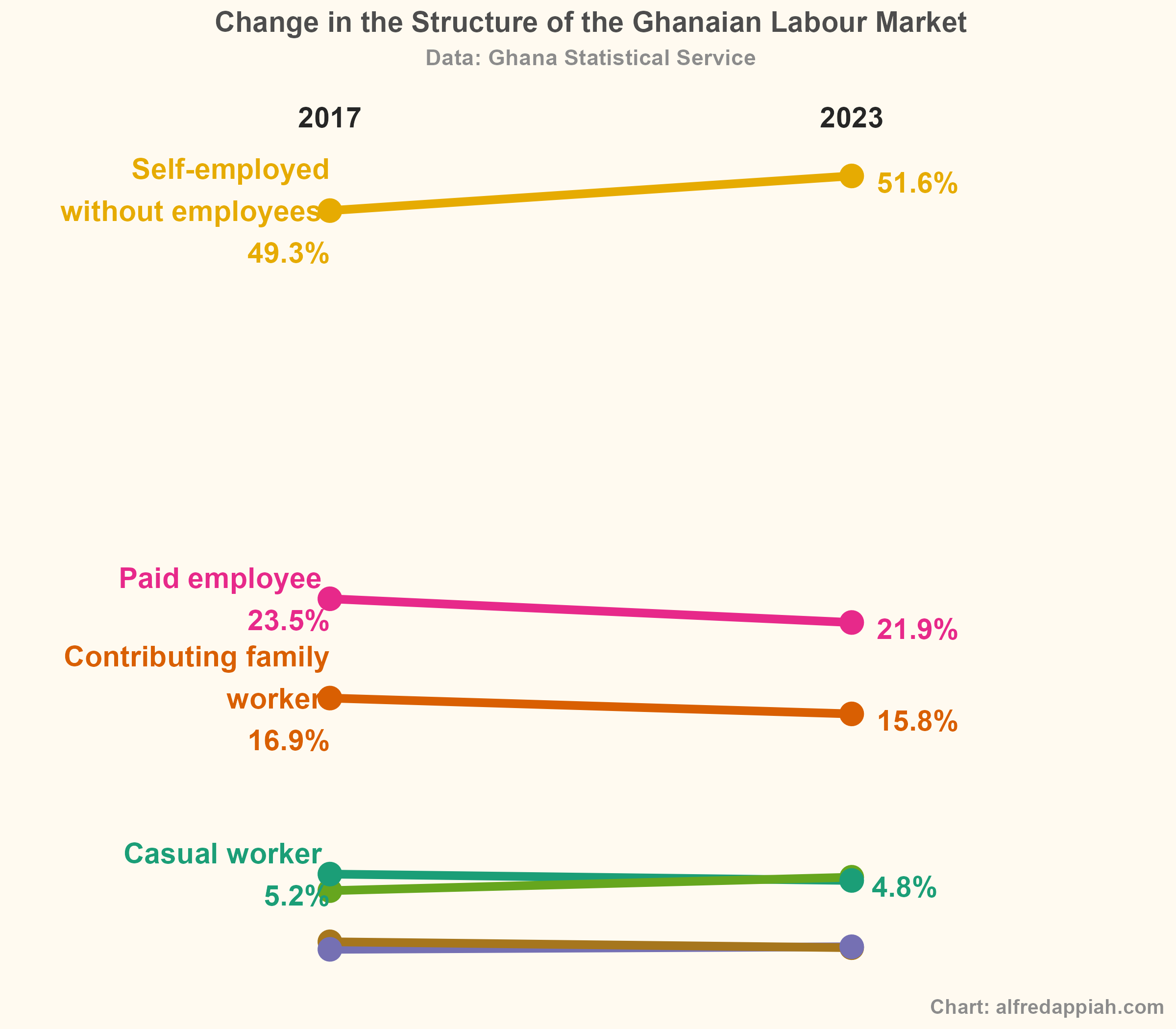

The structure of the labour market hasn’t shifted significantly

The Ghanaian workforce is significantly dominated by self-employed people without employees (aka, own account workers). People in this type of employment situation generally lack decent work, have inadequate earnings and difficult working conditions. The extent to which we are transitioning people to more salaried or wage employment is important. Over the last seven quarters, we haven’t significantly changed that. The share of self-employed people without employees in the total employment population has increased marginally, whereas the share in wage employment has been largely flat.

Looking at the data over a longer time trend doesn’t paint any better picture. In fact, the share of wage employees in total employment has reduced from 23.5% in 2017 to now 21.9%. On the other hand, the share of own account workers has increased from 49.3% in 2017 to 51.6% in 2023. That suggests that the job growth is largely still in vulnerable employment but not in wage employment.

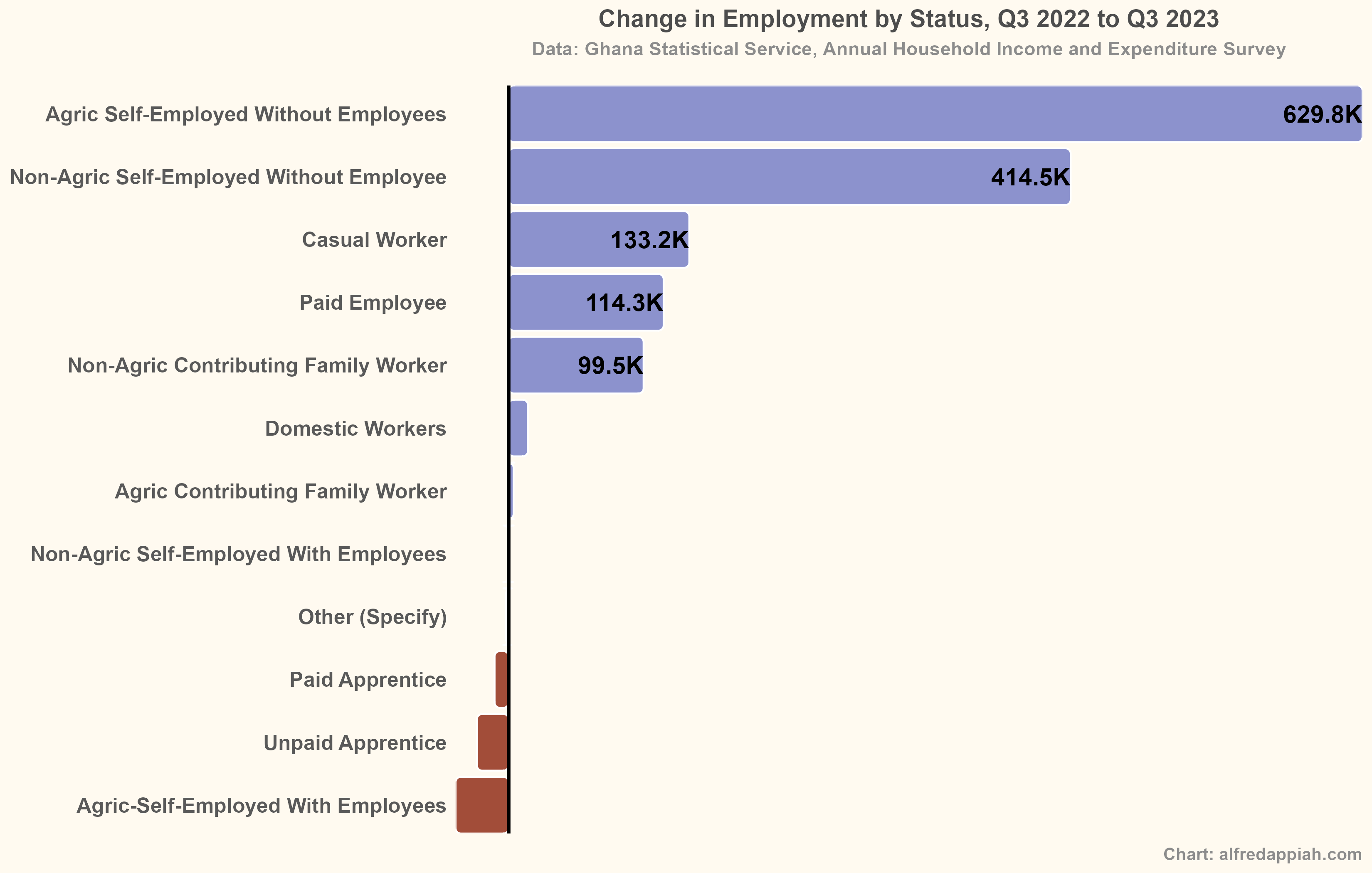

Don’t get me wrong, the Ghanaian economy does create jobs. No doubt about that. The issue is about the quality of the jobs created and how that significantly transforms the labour market, but most importantly how it makes the lives of Ghanaians better.

Don’t get me wrong, the Ghanaian economy does create jobs. No doubt about that. The issue is about the quality of the jobs created and how that significantly transforms the labour market, but most importantly how it makes the lives of Ghanaians better.

So where are the jobs created by current government? I previously wrote a detailed essay on this topic. Most importantly, why are these jobs (in the public and formal private sector) not significantly changing the structure of the labour market? We just saw up there that the share of wage employment has declined between 2017 and 2023. One might say perhaps the government is helping people to set up their own businesses. Well, the percentage of self-employed people with employees has only increased marginally from 4.1% in 2017 to 5% in 2023.

So where are the jobs created by current government? I previously wrote a detailed essay on this topic. Most importantly, why are these jobs (in the public and formal private sector) not significantly changing the structure of the labour market? We just saw up there that the share of wage employment has declined between 2017 and 2023. One might say perhaps the government is helping people to set up their own businesses. Well, the percentage of self-employed people with employees has only increased marginally from 4.1% in 2017 to 5% in 2023.

Since my last article on this topic, I have seen new data that still doesn’t explain the jobs created in the public sector and formal private sector.

Growth in active taxpayer population does not match the jobs created

Between 2019 and 2022, the active employee (PAYE) tax population increased by 542K people. In that time frame, the snippet of an Excel spreadsheet provided by government (the Veep, to be specific, in case we can’t associate him with the government) as proof of jobs created shows that 889K jobs were created. This analysis is even generous because we are assuming here that any new tax payer is a new job and not because of enhanced compliance efforts by the GRA. This generous analysis still doesn’t explain about 40% of the jobs created in the time frame considered. Note that I only had access to GRA data for 2019 to 2022 so I used the corresponding job numbers for that period. These are jobs created by government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) and the formal private sector, and are ‘trackable’ according to government. So why aren’t the vast majority of them reflecting in the active taxpayer population.

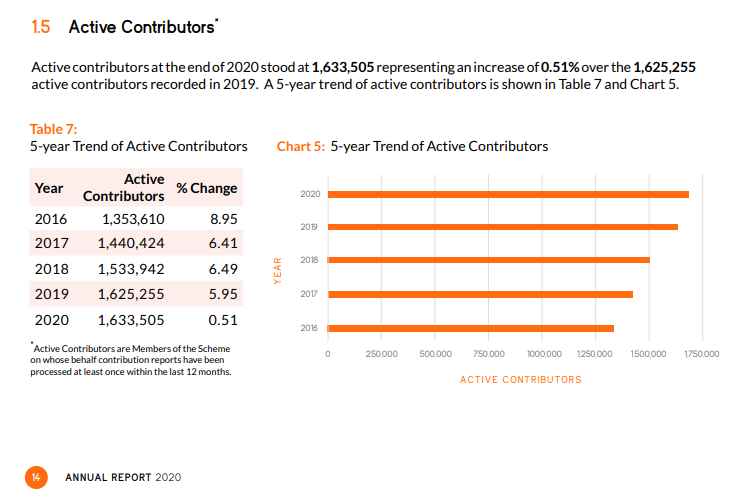

Active SSNIT contribution data does not match the jobs created

Active SSNIT contribution is a decent proxy for conditions in the labour market. The Bank of Ghana uses it to gauge employment conditions. Between 2016 and 2021, the active SSNIT contributor population increased by 380k people. In that time frame, the government’s ‘jobs data’ showed that about 2m jobs were created. In essence, only about 19% of the jobs created showed up in the active SSNIT population. Again, these are jobs created by the public and the formal private sector. In fact, the government said its private formal jobs data is based on SSNIT data. How then do we explain the significant difference between active contribution and job growth? That raises an issue about the sustainability of these ‘jobs’ or whether most of them actually exist. Perhaps, the jobs are largely transitional and not sustainable jobs.

The jobs created can simply not be verified with publicly available data

These jobs that are reportedly created in the public and formal private sector, which would suggest that there is a bit of formality to them, have not led to any positive change in the share of total employment that is wage employment. It does not match growth in active tax payer population and certainly does not match growth in active SSNIT contributor population. So the question still remains, where are the 2.3m or (2.1m depending on which politico is talking about it) jobs created in the public and formal private sector? We will keep digging.